In modern context so much of professional wrestling is critiqued and reviewed based on feats of athleticism. High flying and acrobatics are more popular than ever.

This isn’t just in the early 2000s vein of daring spots where someone might throw themselves from the top of a 30 foot ladder or off of a steel cage. Not the feats we saw from The Hardy Boyz, Edge and Christian, The Dudley Boyz and countless others with midcard status. From the Young Bucks to Ricochet to Finn Balor, the most vocal wrestling fans worship at the altar of cool flips and stylistic dropkicks.

It’s easy to forget that, above all else, pro wrestling is performance art.

The lore of wrestling and the heart of the story is attached more to characterization than move set. Weekly programming has a closer relationship to Shakespearean tragedy- parts good and evil, parts comedic relief- than it does with UFC or Ninja Warrior. Similarly to a Shakespearean tragedy, pro wrestling strives to appeal to the highbrow and lowbrow sensibilities: the nobility who can afford the VIP packages of floor seats to the common folk who sit in the nosebleeds.

No one understands this like Bray Wyatt does.

I’ll forgive you, when it’s done brother.

— WYATT 6 (@Windham6) July 16, 2019

The sickness is gone.

We owe them.

And Yowie Wowie is it gonna be a spectacle!!!

The vehicle of Bray Wyatt’s return to wrestling in 2019, The Firefly Fun House, has roughly eight full segments. The Firefly Fun House is curated visually from the tropes and styles of early childhood programming. Unlike the pairing of The Deleters of Worlds, Bray Wyatt’s tag team gimmick with Matt Hardy in his prior incarnation, these vignettes were not a roughly done may-as-well spot for the performer. This was another volume for The New Face of Fear.

The surface level value is clear. There’s no fourth wall and primary colors abound. A home setting littered with puppet friends connects to the adults in the audience who grew up on Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood or Pappyland. Adding edge and darkness to innocuous content litters Hot Topic and DeviantArt alike. It’s a staple of the internet age, easily recognizable and understood.

But the show has reference after reference to Bray Wyatt’s former exploits. One of the seemingly silliest segments, the workout scene in which Wyatt sings the “Muscle Man Dance,” the so-called witch Abby (the name of the never seen sister who Wyatt has always worshipped, at times despised, and invokes in his finishing move) refuses to engage.

This comes after it was established that the Fun House feels like limbo for her. After an episode in which she gets angry, she’s repeatedly woken by the noise of his new life and later asks, “Why won’t you let me rest?”

Wyatt addresses the audience more than once to apologize for who he was in the past, how bad he was and when a more sinister and less human persona takes hold in glimpses, The Fiend, Wyatt explains, “He’s here to protect us. Sometimes I find it hard to be confident. I find it hard to be brave. Especially when I’m all alone.”

You get as much as you want from the Firefly Fun House. Bray Wyatt’s descent into madness and supernatural spooks from his debut as an unsettling cult leader has gotten weirder and weirder each time he is separated from his “family.” The storytelling before he ever set foot in a ring this year could be a simple delight, a spooky romp, or it could be a rich prologue to a new mythology. Lowbrow and highbrow. It’s up to the viewer.

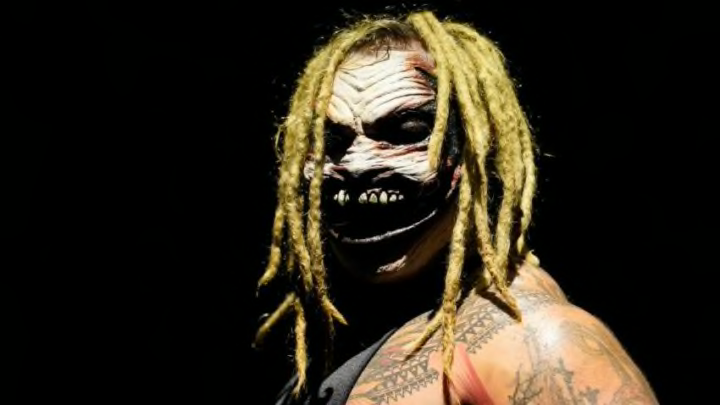

The Fiend’s full entrance and official in-ring debut at SummerSlam brought about undeniable change and recommitted Bray Wyatt to his constant pursuit of power through fear.

“People worship what they fear. Fear is power. Follow the leader,” he whispers at the end of a Firefly Fun House segment.

The lantern that for years has announced The Wyatt Family and the danger they bring with them (“we’re here”) stretched the disfigured head of a face that is immediately recognizable to the crowd, that has been uninterested in win or loss, that has waged psychological warfare with the biggest of performers, even nearly corrupting pro wrestling’s ideological Superman, John Cena.

Professional wrestling is theater in the round, which is, essentially, a theater with no fourth wall. The fans are visible, tangible, touchable. And the performers expect their participation.

Bray Wyatt doesn’t illicit a good time or the respect of his physical feats. He seeks something greater. Emotional response, discomfort, something that goes home with you. With a secondary persona that can entrap the deity of the most terrifying figure in modern wrestling, this story has outdone even The Undertaker and Kane.

The lantern is a symbol, the very figure of Bray Wyatt is a symbol. And now those symbols are props to the Fiend, a character just left of human, whose mantra “hurt and heal” is not pinned down or limited by feel good millennial culture or the PG limitations that keep WWE a family show. In a world hungry for clear motivation, concrete backstory, and Superstar accessibility, Bray Wyatt has refused it all.

And because of that, he defies any poor choice Creative has made or might make. He rejects any lost momentum from injury.

With dirt sheets, Twitter and Instagram adding a human element to wrestlers, and a new pop culture that gives anyone some basic knowledge of wrestling, we’ve forgotten that it’s an art. It’s fun but it’s more than that.

Bray Wyatt doesn’t care if we have a fun time. And he’s a legend for it.